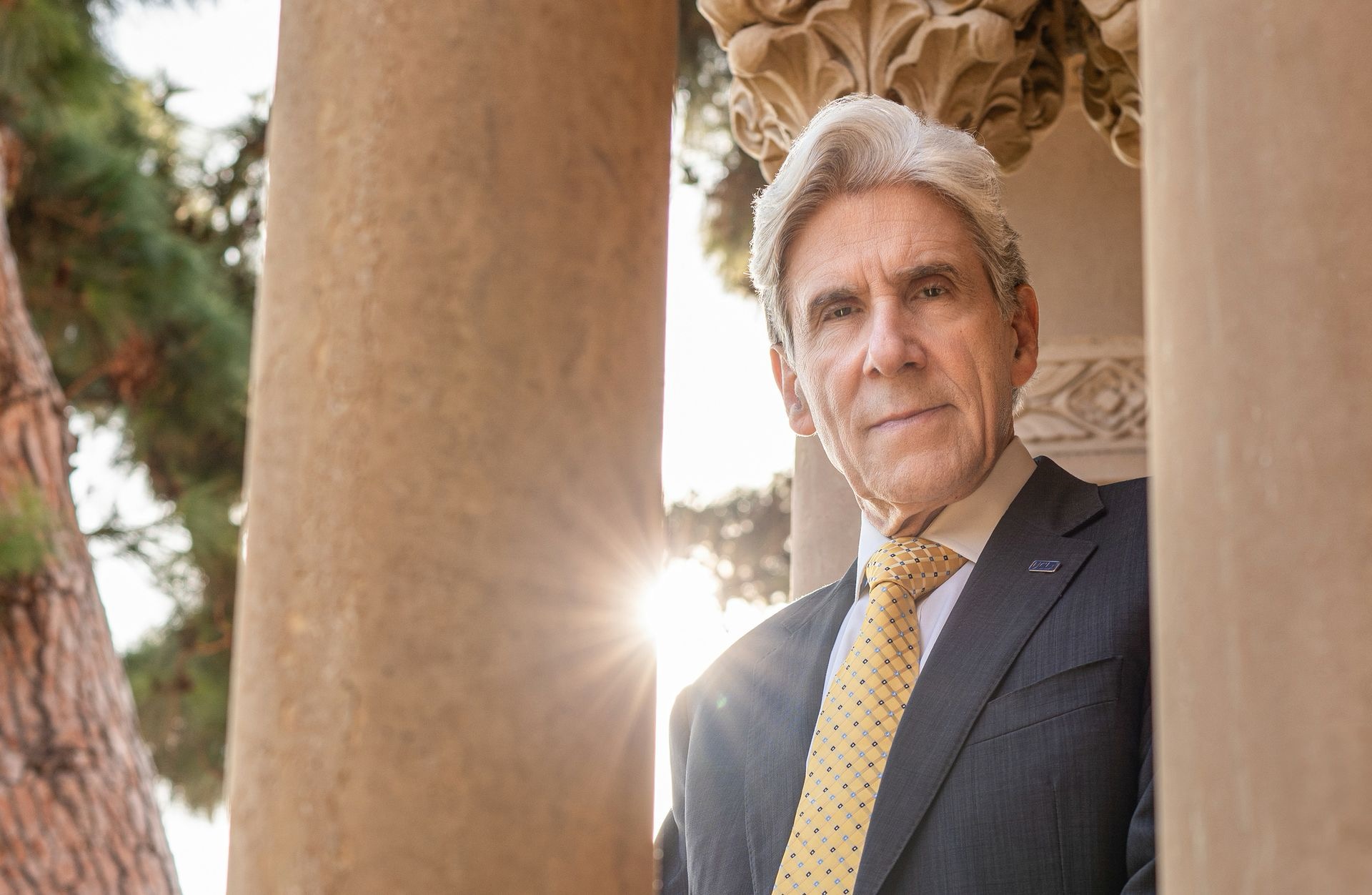

Introducing UCLA’s

seventh chancellor:

Dr. Julio Frenk

I have committed my life to public service in roles that bridge academia, social policy and public health practice across different countries and sectors. I look forward to fulfilling this commitment in new ways at UCLA and in the vibrant, diverse City of Los Angeles.

Chancellor Frenk

UCLA Connects:

Listening Exercise

Chancellor Frenk invites you to join a series of conversations to share your insights, aspirations and ideas to shape our collective vision for UCLA’s future.

About the office

The chancellor of UCLA sets the vision and strategic priorities for the university, ensuring that it can effectively carry out its mission of education, research and public service. Julio Frenk took office as UCLA’s chancellor on January 1, 2025.

Share your thoughts with the chancellor

Chancellor Frenk and his staff welcome the UCLA community’s feedback on campus priorities and the university’s direction.